On Resolutioning

"for here there is no place that does not see you"

I wrote this during a previous calendar change. It still says what I need to hear, and so does Rilke. Happy New Year!

You must change your life.

These words first came to me from a poem at the end of a year, arriving just in time for the annual ritual I dismissed as pointless. They speak not of gentle self-improvement or casual promises, but of demanded transformation. This demand is still in my head now, as 2026 dawns and millions of us engage in the ritual of resolutions.

I used to be one of those unserious people who scoffed at resolutions, suggesting like so many others that if you really wanted to make a change in your life that you can do it any day you wish.

Then I encountered Rilke’s poem, and these five words rearranged something.

January 1 is an arbitrary choice and just another day like any other. This argument is just as considered as suggesting we try Christmas in April or move the US capital to California. Not everyone who skips resolutions scoffs at the idea. Some people don't think much about them at all. And then there are those super rare high agency people who really don't need them, because they see a needed change and immediately start marching towards it. I think there are very, very few of those people.

The new year is a time for new beginnings, and some of the power is in the arbitrary commons of the date. We all wait for the ball to drop. We all start training our brains that it really is 2026. We all stop to celebrate. We all start over in some way. And we’re offered the chance to let reality tell us something about ourselves.

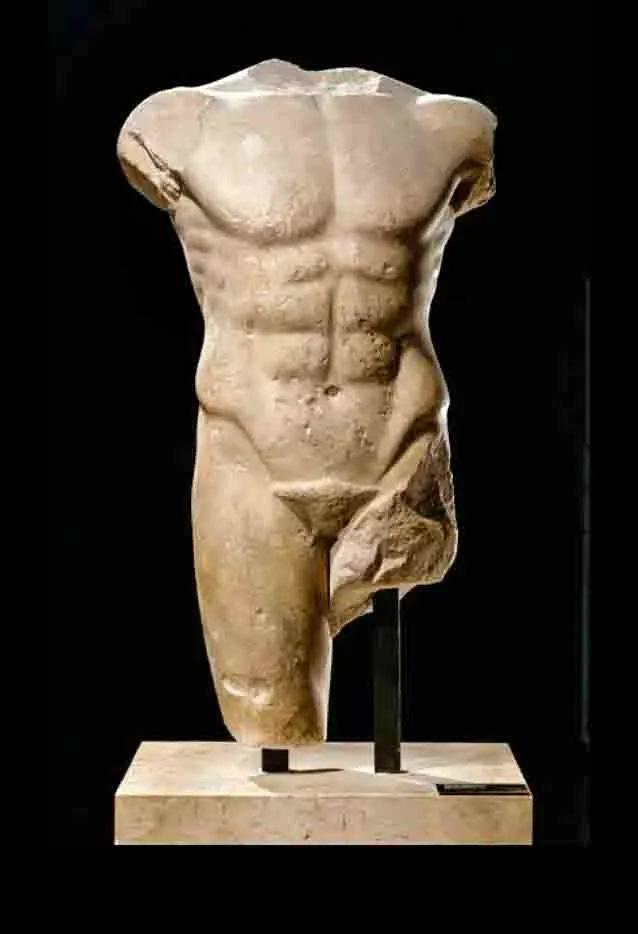

Rilke's Archaic Torso of Apollo describes a broken statue, headless and ancient, yet somehow radiating an impossible vitality. I read it over and over and over. What seized me wasn't just Rilke's imagery, but the shocking final line that seems to come from nowhere and everywhere at once:

You must change your life.

What makes this command so powerful, as Douglas Murray beautifully articulates, is that it emanates not from the viewer's mind but from the statue itself. The broken torso of Apollo speaks. And it isn't a gentle nudge — it is beauty reaching out and demanding transformation. The statue blazes with such power that we cannot remain unchanged in its presence.

You must change your life.

In some way, this year was for me an ongoing meditation on this poem. The idea that truth and beauty might have something to say to us—that they are active forces in the world rather than absorbed passively—is antiquated. We remember beauty only occasionally, too busy rushing past enraptured in our own maturity to be enraptured by something else. These ideas are as old and dry as our grandfather’s parchment-thin skin, and like him, we assume they have nothing left to say to us. The prophets of the Greatest Generation—ironically, those most steeped in the terror and despairs of the 20th century—are old or dead. Our culture has only a vague memory of the sway truth and beauty once had.

It’s up to us now.

The great questions from the Greeks to the Enlightenment were asked out of wonder, not necessity. What is the purpose of reality? Of truth and beauty? Of evil? Of suffering? Of ourselves? The universe is the Answer, but it’s an ever-unfolding series of mysteries that we’re only ready to understand when we ask the right questions. Our privilege as humans is that we have agency to help shape both the answers and the ongoing questioning. Reality is begging us to act. Truth and beauty are how she speaks to us.

The critical debate of our time is: do we even acknowledge these questions? Rushing around late to our meetings while staring down at the videos on our pocket-sized screens, are we capable of hearing through our headphones the message the statue of Apollo whispers? Or is our attention too saturated and too divided to even recognize that truth and beauty exist?

The modern human impulse is not an outward motion towards reality, but an inward sweep towards a virtual hologram. We live today in a digital panopticon of our own shared making. Plato’s Cave built with silicon wafers, filled with shadows more alluring than he could have imagined, where desire and acceptance are more important than virtue or goodness.

We need to change. I need to change. This idea of change is not one that divides humans into groups; it’s an idea that divide our hearts. We each have a side that is yearning to listen for the divine whispering in our everyday reality. And we have another side, eager for dopamine, ready to be molded into what the mob demands of us. Each side is an animal ravenous for the activity and attention that will make it grow. Which animal will be fed?

You must change your life.

Listen to what I shall call Him: the Bottomless Abyss, the Insatiable, the Merciless, the Indefatigable, the Unsatisfied. He who never once said to poor unfortunate mankind ‘Enough!’

‘Not enough,’ that is what he screamed at me.

‘I can’t go further,’ whines miserable man.

‘You can!’ the Lord replies.

‘I shall break in two,’ man whines again.

‘Break!’

— St. Francis by Nikos Kazantzakis