The Return of Magic

The Library and the Casino

“Many gnostics, on the contrary, insisted that ignorance, not sin, is what involves a person in suffering.” — Elaine Pagels

The Window

There’s a concept that gets discussed in high-IQ societies but rarely escapes into the wider world: the window of comprehension.

The idea is straightforward: people can genuinely follow each other’s reasoning within about a 2 standard deviation range. Roughly 30 IQ points. Inside that window, you can disagree, argue, convince, be convinced. The other person’s logic is visible to you, even when you think it’s wrong.

Outside the window, something different happens. The reasoning doesn’t become wrong. It becomes invisible. You hear the words but the connections don’t land. The leaps that seem obvious to one person are simply absent for the other. You’re not in a debate anymore. You’re in parallel, non-overlapping monologues.

And it goes both ways.

The person three standard deviations above average finds the average person’s reasoning just as opaque as the reverse. It’s not that one is right and one is wrong. They’re alien to each other. Each is trying to communicate across a gap that neither fully perceives, and both walk away frustrated.

People deservedly hate this idea. It’s overgeneralized and, coming from high IQ societies, it lands as a sort of intellectually aristocratic aspersion. But the overly general idea still has some kernel of truth. You wouldn’t expect to be able to describe a car to a dolphin. And a dolphin could never explain its field of view from echolocation.

The window describes fit. The relationship between minds. Some minds fit together well enough to genuinely reason with each other. Others don’t.

Once you see it that way, you realize the idea actually applies to the systems people talk about. So what happens when the world itself—the institutions, the economy, the information environment, the cascading abstractions that run everything—what happens when all of that falls outside your window?

There are two ways this happens, and only one of them is about raw capacity.

The first is straightforward: some systems are complex enough that below a certain cognitive threshold, they simply can’t be modeled. The causal chains are too long, the abstractions too layered, the feedback too delayed. For some people, like it or not, certain parts of the modern world are genuinely beyond reach.

But there’s a second mechanism that affects everyone, regardless of capacity: specialization. Even if you could understand how the financial system works, you probably don’t have time—because you’re busy understanding your own field, your own domain, the systems you’ve chosen to make legible. Nobody can model everything. The world has gotten too large. So even the brilliant physicist relies on trust when the plumber shows up. Even the doctor defers to the accountant on taxes. We all live in a world that’s partially magic, by necessity. The question is how much, and in which domains, and whether we’ve made good choices about where to place our trust.

This means the problem of legibility isn’t just about who can understand what. It’s also about the growing number of domains where everyone has to trust without verifying. The specialization that makes modern expertise possible also makes modern dependence unavoidable.

The high-IQ societies want to believe they’re special and IQ is simply built-in. But this window can move substantially.

Not without limits… you can’t read your way to Ramanujan if you weren’t born with it. Hardware matters. But within a range and how much of your capacity you use and how wide a world you can inhabit… that’s shaped by what you do. The window moves with practice.

Reading is the clearest example: it expands the world you’re capable of seeing. Our universe is wildly complex and full of nuance, so much so that it can take hundreds of pages to capture a single subject properly. Some things can only be understood with that level of investment.

This points to something startling: people who read live in an entirely different world than people who don’t.

Literally different! The same street, the same job, the same headlines, but experienced through a thicker mesh of concepts, a richer causal map. The person who has spent thousands of hours building mental models through sustained attention sees more. Because they’ve built the equipment.

Every time I hear of someone who doesn’t read, I think of one of my favorite lines from Hamlet: There are more things in Heaven and Earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy. How much of the world is simply missing for someone who never gave themselves the tools to see it?

And it’s not just volume. It’s range.

Aristotle said it’s the mark of an educated mind to entertain a thought without accepting it. Authors who argue against prevailing thought have a larger task than the mainstream voices. They can’t assume agreement. They have to show more of their work, provide a fuller picture, anticipate the objections. Which means reading them forces you to model a mind that doesn’t share your assumptions.

One of the biggest dangers of our time is that we no longer tolerate those who disagree with us. We sort ourselves into echo chambers and sneer at the other side. But that sorting narrows your window. Every mind you refuse to model is a piece of the world you’ve made invisible to yourself.

This window can move in either direction.

And the default information environment we’ve built for ourselves—the algorithmic feed, the engagement-optimized content, the endless scroll of takes and reactions—pushes it downward.

Not because people are stupid. Because easy is easy. The algorithm serves what captures attention, not what builds capacity. It’s designed to keep you looking. Every hour surrendered to the feed is an hour of eating fast food while avoiding the gym.

And it’s hardest when you have the least practice. The people who most need an expanded window are exactly the ones most likely to have it narrowed because the feed is right there, asking nothing of you.

The doing is the becoming. And right now the systems are built to reward doing the easy thing.

And so most people are becoming less.

The Peasant and the Physicist

Picture a village in the 1850s. A peasant farmer and a university-trained physicist live within a few miles of each other. They share the same countryside, the same market square, the same sky. Maybe even the same church.

They do not share the same world.

The peasant lives inside a universe of local causation. He understands the relationship between rain and crops, between work and harvest, between the blacksmith’s hammer and the horseshoe it produces. When things get strange—disease, drought, the distant decisions of kings—he reaches for explanations that match his experience: providence, fate, punishment, blessing. The margins of his world are populated by forces he cannot see and does not pretend to understand.

The physicist sees mechanisms. Forces with predictable behaviors. Regularities that can be measured and modeled. Where the peasant sees the will of God, the physicist sees thermodynamics. Where the peasant accepts mystery, the physicist poses questions.

Two parallel universes, occupying the same timeline and the same space.

But notice something about that village: the physicist’s knowledge wasn’t hidden. The books existed. The university lectures happened. In practice, of course, the peasant couldn’t access them. Twelve hours a day in the fields, six or seven days a week. The information existed, but behind barriers of time and geography and class that made it unreachable for most.

Those barriers have eroded. By the 20th century, the capable kid from a poor family had a path, if they wanted it. What that kid didn’t have was a device in their pocket competing for every spare moment of attention. No algorithm sorting them into engagement-optimized realities. No feed filling the boredom that might have driven them to the stacks.

The peasant couldn’t access the information.

A kid in the 1900s could, if they chose to.

A kid today has access to everything, all of human knowledge. And an environment designed to ensure they never sit still long enough to use it.

When causal chains exceed your capacity to model them, the world functionally becomes magic. This is magic as operational reality, not metaphor.

Think about what magic actually is in stories. Events happen without visible mechanism. Effects appear without traceable cause. The wizard waves his hand and fire emerges. You can observe the result but you cannot replicate it, predict it, or learn to control it. The causal chain is hidden from you.

What’s it like to live in a world where you can’t model the systems you depend on?

You can’t predict. You try things and outcomes seem random, disconnected from your actions. You can’t learn from feedback, because you can’t see the connection between what you did and what happened. You can’t act strategically, because strategy requires a model of cause and effect that you don’t have access to.

All you can do is narrate. Tell stories about why things happen. Assign agency to characters—the villains and heroes, conspirators and saviors—because characters are easier to model than systems. Stories provide the emotional closure that understanding would provide if you had it.

Magic is what complexity looks like when models fail.

The 19th-century peasant lived in a partially magical world driven by weather, disease, and the machinations of distant rulers. But most of his daily life was legible to him. He planted seeds and crops grew. He worked his field and food appeared. The relationship between effort and outcome was visible and direct.

He didn’t understand how the economy worked. But the economy didn’t ask him to have an opinion about it. His beliefs about distant matters were locally wrong but globally irrelevant. He couldn’t vote on monetary policy. He wasn’t exposed to hourly updates about international conflicts he had no power to affect. The world beyond his village was mysterious, but it largely left him alone.

His ignorance was not fatal to the coherence of his life.

A 19th-century peasant did not understand the world, but neither did the world require his understanding.

Then the world changed.

Not all at once, and not evenly. But somewhere between that 1850s village and now, the amount of abstraction required to understand ordinary life started climbing. And it hasn’t stopped.

Consider what you’d need to genuinely model to navigate your own life. How does your money work? Not just “I have cash and when I hand it over I get a thing,” but: What is the Federal Reserve doing? Why does inflation happen? Why is that thing more expensive now? How are rates changing? What about fractional reserves? How do commercial banks validate their systems and your accounts? What does it mean that your retirement is invested in index funds that own fractions of companies you’ve never heard of, managed by algorithms you’ll never see?

Now do this for your job. And then your government. And your food supply. And how your phone works.

Most importantly: how does information reach you? Through which filters, which algorithms, which editorial decisions, which financial incentives? What data center decided which story would be at the top of your feed? When you read the news, whose attention is being bought and sold?

The amount of abstraction required to answer these questions keeps rising. And most people can’t answer them.

IQ scores rose throughout the 20th century. This is called the Flynn Effect and it’s well documented. Each generation scores higher than the last, roughly 3 points per decade. By that measure, we’re smarter than our grandparents, who were smarter than theirs.

And yet…

More people seem to be falling below the threshold where the world makes sense to them. Not because they got dumber, but because the threshold moved. The complexity of the systems we must navigate rises faster than our capacity to model them. The legibility line climbed up and we didn’t climb with it.

Think about what that means. Your great-grandfather probably had a lower IQ score than you. But the world he lived in was far simpler. The ratio of his cognitive capacity to his environment’s complexity might have been better than yours. He could model his world. You may not be able to model yours.

We got smarter. But the world got opaque faster.

The 19th-century peasant didn’t understand the world. But he wasn’t expected to. His ignorance was contained. He lived downstream of systems he couldn’t see.

The modern citizen lives in a different situation. We’re embedded in global systems we cannot observe. We vote, react, organize, share opinions—all inside abstractions we can’t model. We can influence systems we don’t understand. Our beliefs propagate through networks and amplify in ways we can’t track.

The peasant’s ignorance was locally wrong but globally irrelevant. Ours feeds back. Our confusion becomes part of the system. Our narrative substitutions enter the discourse. Our votes shape policy we can’t evaluate.

The world didn’t require the peasant’s understanding. The modern world seems to demand ours, even though we don’t have it and aren’t being given the tools to develop it.

So what happens when the world persistently exceeds our window of comprehension?

Certain things start going wrong in predictable ways.

The connections disappear. We can’t see how our actions relate to outcomes. We work hard and things don’t improve. We follow the rules and get screwed anyway. We try to do the right thing and it makes no difference. The feedback loops are invisible or so delayed they seem random. Cause and effect, the most basic tool of learning, stops working.

Stories replace models. When we can’t trace causal chains, we reach for narratives instead. “They’re lying to us.” “The system is rigged.” “Experts can’t be trusted.” These are compressions, not stupid conclusions. Narratives reduce an incomprehensible situation to characters with intentions: villains and heroes because characters are easier to reason about than systems. Stories give us someone to blame and someone to believe in. They provide the emotional closure that understanding would provide, if we had it.

Agency drains away. The world starts to feel like something that happens to us rather than something we participate in. “Nothing I do matters.” “It’s all decided somewhere else.” “The game is fixed before you start playing.” Is this laziness? Or is it the rational response to a situation where we can’t see the levers? If we can’t model how the machine works, why would we believe we could affect it?

These three—causal opacity, narrative substitution, loss of agency—form a modern syndrome. They feed each other. The less you can see the connections, the more you reach for stories. The more you rely on stories, the less you develop actual models. The worse your models, the more powerless you feel. The more powerless you feel, the less you try. And the cycle continues.

This syndrome is spreading.

Not because people are getting dumber. Not because they’re lazy or incurious or somehow morally deficient. It’s spreading because the environment changed and the organisms—individuals and societies—didn’t change fast enough.

The world got harder to see. The models required to understand it became more abstract and mathematical, more dependent on specialized knowledge that takes years to acquire. The systems became more interconnected, with longer causal chains and delayed feedback. And all of this happened while the information environment got noisier and more optimized for engagement than understanding.

We built a world that exceeds the cognitive capacity of most of the people living in it. And then we act surprised when they reach for narratives and get angry at systems they can’t comprehend but are still judged against. This is why populism surges. This is why “burn it down!” has appeal across the political spectrum.

And the information environment isn’t getting simpler.

So the syndrome is spreading, and the environment is getting worse. Who does this affect most?

Let’s start with the outlier geniuses. These are the people so far out on the curve they can handle practically any amount of complexity. Consider Srinivasa Ramanujan. He was a clerk in Madras with almost no formal training, scribbling impossible theorems in notebooks, writing letters to Cambridge mathematicians who mostly ignored him until one didn’t.

I always think of Ed Witten too, mostly because he came from my own backyard in Baltimore. He was a history major, briefly a journalist, found his way to physics, and ended up winning the Fields Medal (in math) as a physicist.

We love to focus on these sorts of geniuses, five, six, or more standard deviations from normal, because they make a great story. They have preternatural gifts that surface despite everything. An underdog story. Thank goodness they were found.

But Ramanujan and Witten are the wrong people to focus on.

The internet solved the Ramanujan problem. A kid today with that kind of mind almost anywhere in the world has access to Wikipedia, to Math Olympiad archives, to online communities full of people who would recognize what they were seeing. The modern world is very good at surfacing extreme talent. If you’re genuinely six standard deviations out, someone will find you.

The geniuses mostly make it.

The real margin is somewhere else.

Think about the person at two or three standard deviations above the average. Roughly 130 to 145 IQ. Not one in a million—more like one in 50 to one in 1000. Smart enough to be in the room but not so smart that the room rearranges itself around them.

This person has the capacity to model most systems if they put in the work. They can learn the abstractions. They can update their beliefs when evidence changes. They can sit with uncertainty without immediately reaching for a story to make the discomfort go away.

This person can navigate the modern world legibly. The rising threshold hasn’t outrun them. They could cross over, if conditions allowed.

But conditions often don’t allow.

The algorithm competes for their attention from the moment they wake up. The information environment rewards reaction over reflection. And the threshold itself keeps climbing toward them.

The person who could cross over often doesn’t, because crossing over is hard and the alternative is right there in their pocket, and easy.

Ramanujan needed certain things to become Ramanujan.

He needed Carr’s Synopsis of Elementary Results in Pure Mathematics—a dense, eccentric book that presented results without proofs, forcing him to derive them himself. He needed unstructured time to obsess. He needed productive isolation, the kind of boredom that forces you inward because there’s nowhere else to go.

The algorithm is an anti-pattern for all of this. It serves content designed to capture attention, not develop capacity. It fills every gap, every moment of boredom, every stretch of unstructured time. It prevents the very conditions that would force someone to turn inward and build.

Ramanujan was far enough out that he probably would have made it anyway. His obsession was too strong to be captured. But what about the kid at +2 SD? What happens to him when the algorithm gets to him at eleven?

They become content consumers. They aspire mostly to be content creators. They develop opinions instead of models. They react to the discourse instead of building the equipment to see past it. And nobody notices, because they’re not dramatically gifted enough for anyone to track what they could have become.

The Ramanujans are too far out to capture easily, and the world finds them anyway.

The danger is the much larger population who could be above the magic but get captured early. The +2 SD kid who spends their teenage years on content instead of books. The +2.5 SD adult who retreats into narrative because modeling is exhausting and the feed is always there, distracting her.

These people matter. Not because they would have been geniuses, but because they’re the population that could understand how things work. They could model the systems everyone else experiences as magic. They could be the engineers, the doctors who actually think, the managers who understand what they’re managing, the citizens who can evaluate policy instead of just picking a side.

We still produce loads of these people. The world has incredible engineers, doctors, systems thinkers. The question is direction: are we getting more of them, or fewer? And for everyone at this cognitive level, it’s a matter of degree: how much of their time goes to the algorithm, how much to building?

So the question becomes: are we building environments that maximize capacity? Or environments that maximize engagement at capacity’s expense?

Somewhere right now, a kid who could model how the world works and then change it is scrolling instead of reading. They won’t become stupid. They’ll become normal. And normal, increasingly, means magic.

The Political Consequence

When enough people fall below the legibility line, strange things start happening at the level of society.

Expertise starts looking like priesthood. Doctors and public health officials speak with confidence about systems we can’t see, using language we can’t parse, reaching conclusions we can’t verify. Trust requires evaluation, but evaluation requires models we don’t have, so we’re stuck choosing between faith and suspicion with no middle ground. Rules feel arbitrary, ritualistic rather than instrumental; we can’t trace the logic, can’t see why this regulation and not some other one. Authority takes on an occult quality, with confidence disconnected from anything we can see.

And so conspiracy competes on equal footing. If we can’t trace the causal chains, then the expert’s account and the conspiracy theory are both just good stories. One is endorsed by institutions we may or may not trust. The other at least has the virtue of assigning blame to someone. Neither is checkable. People pick the one that fits their priors.

None of this happens because people become irrational. It happens because their rational tools stop working at the required scale.

Revolutionary feeling has a specific shape, and it doesn’t come from poverty.

People tolerate being poor. They tolerate hardship and inequality, as long as the connection between effort and outcome remains visible. As long as the game, however rigged, is at least legible. As long as we can see the levers, even if we can’t pull them.

What people can’t tolerate is being embedded in systems they cannot model while those systems continue to judge them. Power exists, you can feel it operating on your life, but agency does not. There are no levers. And yet we’re still blamed when things go wrong.

That combination is psychologically unstable. People who feel morally implicated but strategically blind, constantly judged by forces they can’t influence… those people don’t ask for reform. They ask for reset. Burn it down. Start over. At least the rubble would be easy to understand.

This is why revolutionary energy often targets institutions that are, by most measures, actually functioning. The institution’s competence is irrelevant if its competence is invisible. The hospital might be saving lives, but if the billing system is opaque and the decisions seem arbitrary, it feels like a machine designed to extract from you. The fact that it’s also healing you doesn’t register the same way.

Revolution is not a demand for redistribution. It is a demand for legibility.

Maybe the old priesthood—the institutions—actually worked.

If the world is functionally magic for a significant portion of the population, then treating expertise as priesthood wasn’t a bug. It was the load-bearing structure.

Think about what priesthood actually provided.

It provided legibility by proxy. You didn’t need to understand the causal chains yourself. You just needed to trust that someone did, and defer to them. The doctor knows. The engineer knows. The institution has this handled. This wasn’t only for people who couldn’t understand: specialization makes trust unavoidable for everyone.

Institutions gave that trust a stable form.

It provided stable heuristics. “Do what the doctor says.” “The engineers approved it, so it’s safe.” “The FDA, the Fed, the CDC, they’ve looked at this.” Simple rules for navigating complex systems. Functional compressions that let you get on with your life.

And it contained anxiety. If the priests are handling the magic, you can stop trying to understand it yourself. The illegibility becomes their problem, not yours. You can focus on the parts of life that remain legible to you and trust that the rest is being managed.

This is what we destroyed.

Not expertise itself… that still exists, maybe more than ever. What we destroyed was the social permission to defer. The implicit contract that said: you handle the complexity, I’ll trust you, we both benefit.

Now everyone is expected to have opinions about epidemiology, monetary policy, climate dynamics, foreign conflicts. People get mad if you don’t have an opinion—the right opinion. Not because they’ve developed the capacity to model these systems—they haven’t and they can’t—but because the information environment demands engagement. Every issue requires a take. Every crisis requires a side.

There’s an irony here. We live in an age of hyperlegibility, as defined by Packy McCormick, but it’s pointed the wrong direction. The algorithm knows your preferences, your triggers, your scroll patterns. You are perfectly modelable. But the systems that model you remain opaque. You can’t see how the feed is constructed, why this content and not that, and that asymmetry is the point. The one who can model the other has power. We’ve made ourselves maximally readable while remaining unable to read the systems that read us. People are engaging with politics and news and the world, but at the level of tribe and signal, not mechanism and system. They’re legible as consumers and signalers. Not as thinkers. Not as citizens.

So the person for whom the world is magic now faces two options:

Option One: defer to expertise. But this feels weak, especially when the experts seem to disagree with each other, when they’ve been wrong before, when trusting them requires trusting institutions that have burned you in the past. And which experts? The ones on TV? The ones your friends trust? The ones endorsed by the tribe you belong to?

Option Two: substitute narrative for model. “It’s rigged.” “They’re lying.” “Trust your gut.” At least these are simple. At least they give you someone to blame and don’t require you to admit you can’t understand the systems that run your life.

Option two is winning. Not because people are stupid. But because we removed option one as a socially viable choice and didn’t provide anything to replace it.

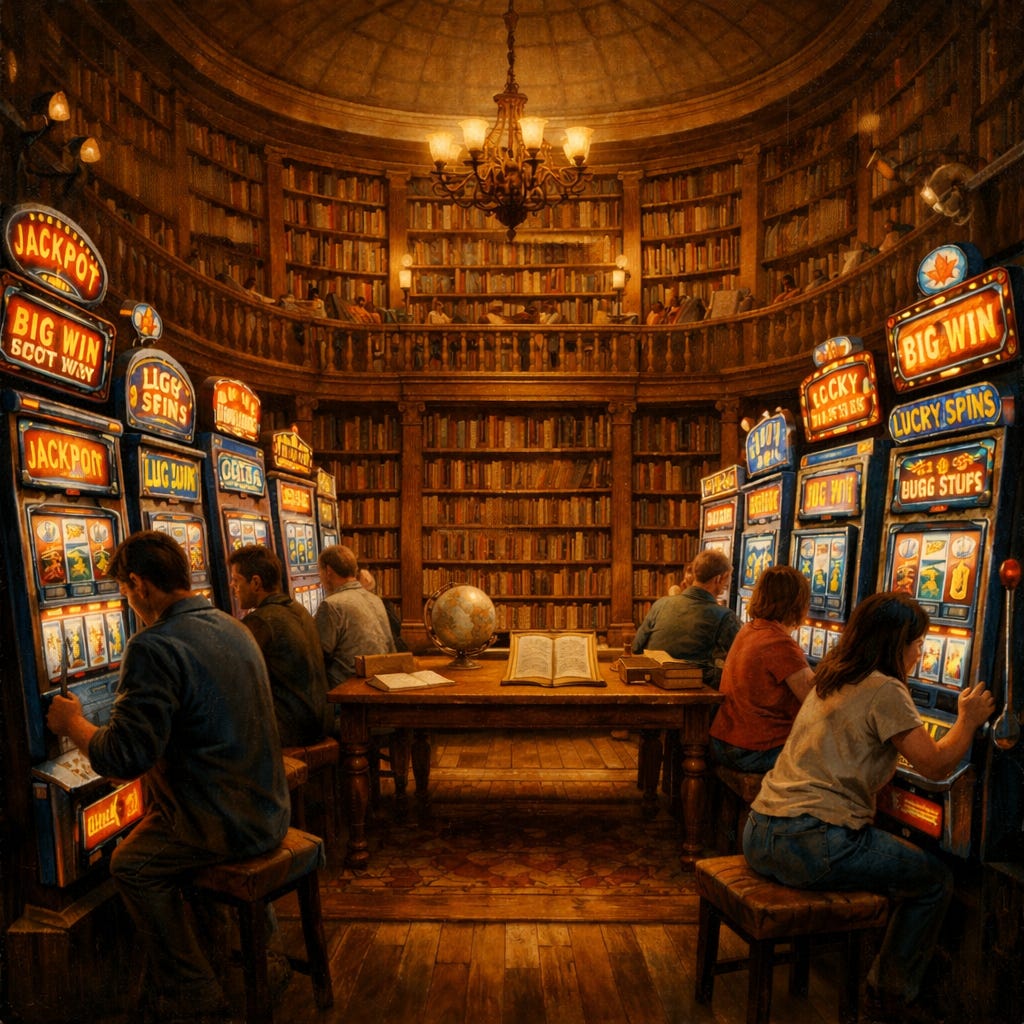

We gave everyone the library and surrounded it with slot machines. Then we wondered why they played the slots.

The Question

So we return to the window.

The question was never whether some people are smarter than others. It’s uncomfortable to say out loud, but it has been true forever and will remain true. The question is whether the world still fits inside enough people’s windows. If it doesn’t…if too many people are living in systems they can’t model… then something has to give.

Because the window of comprehension isn’t just about people understanding each other. It’s about whether people can understand the world they live in. And right now the windows are getting smaller. People are getting smarter but the world is accelerating away from all of us.

The window is expandable to a large degree.

Reading expands it. Discomfort expands it. Sustained attention and the willingness to sit with things you don’t understand until you do—all of this pushes the window. The doing is the becoming.

Nobody is stuck. But nobody fully arrives, either. The window isn’t something you open once… it’s always widening or narrowing depending on how you spend your time. The question is which direction you’re moving.

But.

The environment pushes the other direction. The algorithm optimizes for capture, and the path of least resistance leads to squalor.

Some environments make it easier to be relentless. The kid with the right book at the right time, the adult who finds a community that rewards thinking over reacting… for them the world is beautiful and exciting. The doing is the becoming.

Other environments make it nearly impossible. For people trapped in those environments, the world keeps receding. It takes all the running you can do to keep in the same place, said the Red Queen.

Our current environment, on balance, makes relentlessness harder. It captures more than it develops. It narrows more windows than it expands.

A society can survive inequality. People have tolerated vast differences in wealth and power throughout history, as long as the systems that produced those differences remained legible.

Loss of power is tolerable. The serf knew he was a serf. The greengrocer knew the Communist system. The arrangement was brutal but legible.

Loss of knowing whether you have power—that’s different. That breeds something darker. Rage that has no target. Nihilism that can’t be argued with. Apocalyptic longing for a reset that would at least produce comprehensible rubble. Purity movements that promise to burn away the confusion.

We’re seeing all of these. And we’ll see more, unless something changes.

The relentlessly interested will still rise. Ed Witten made it. Ramanujan made it. Somewhere right now, a kid is finding their way to problems hard enough to transform them.

But the threshold for modeling and relentlessness keeps climbing. The forces pulling the other direction keep strengthening. And the number of people captured is growing.

The question isn’t whether genius will emerge. It will, always. The question is whether we can build environments that actually expand our understanding of the world. That make the hard path findable for the one-in-fifty, not just the one-in-a-million—and then keep pushing.

This means working from both directions. We need to focus on the hard intellectual stuff. Reading still works, sustained attention still works, discomfort still builds capacity. But we also need to make the systems more legible, not less. Institutions that can be understood by the people who must navigate them. Information systems that serve truth, not engagement.

And this helps everyone, not just those at some point in the distribution. The physicist can’t evaluate his own YouTube feed. The doctor scrolls her Instagram as blindly as anyone. We all live in partial magic. The question is whether we’re building systems that require less of it. Not necessarily simpler, but comprehensible. Open source software works not because everyone reads the code, but because anyone could, and enough people do. Legible systems work the same way. They don’t require universal understanding. They require the possibility of it.

That’s how you defuse the revolutionary impulse: not by restoring the old priesthood, but by building systems that need fewer priests to interpret.

The peasant lived in a world of magic because he had no choice. The systems exceeded his capacity and no one expected otherwise.

We’re building a new world of magic out of abundance. We gave everyone the library. We’re just making it harder every year to sit down and read.

But the library is still there. And it’s better than ever.