The Skills We're Destroying Are Becoming Priceless

The new world is all about tokens.

Let me tell you about my writing workflow these days. I'm sure you'll be very surprised to know that it involves some prompts.

I always have ideas flowing when I'm driving or when I'm walking, and I've never been able to capture them well. I'd scribble some keywords in a draft email or a note and have no idea what I was thinking hours later. But voice transcriptions have gotten so good that I just turn on the mic and start talking. I use Reflect to capture it all and I get crisp text for all of my many crazy thoughts.

So now what? Here's where the prompts start. When I'm ready to write, I take my voice transcript - which is a complete mess by the way - and I feed it to my brainstorming prompt. And I get back the key insights, themes, and a proposed outline structure that helps make a compelling narrative. And I'm ready to write.

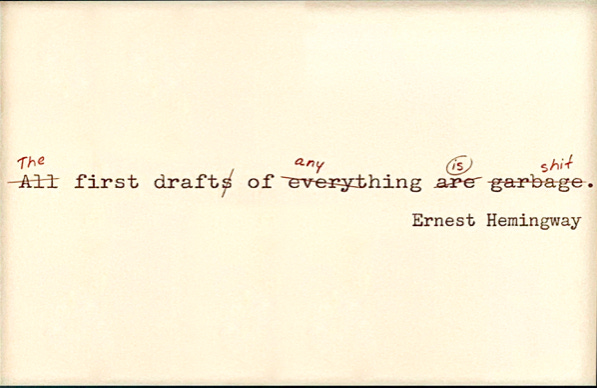

The first draft is all human, no cyborg.

Once I've got something down, it's back to AI collaboration. And I feed this to my editor prompt. What I get back is both sycophantic genius posturing and brutal exposure to my weaknesses. But it's the right combination of compliment and criticism to get me from first draft to final.

My brainstorming prompt is 700 words. The editor prompt is over 800. But I'm not treating them as words I need to read. I'm treating them as collections of tokens.

It's a similar story when I'm working in Cursor, "writing" code. I've made a transition with an AI next to me - where I used to care about the details of every line, now I worry about big chunks of text that get moved around and represent higher abstractions. It's not about getting the details of a specific function call or template format right: the LLM will do that. Now it's about orchestrating these actions. Many software engineers will bristle at this, but we're moving to a world where you just need to read code; you don't need to write it.

Here's what's really happening: AI has pushed humans up the abstraction stack. I've been pushed up to operating at the prompt level, the chunk level, the system level. My 700-word brainstorming prompt isn't just longer; it represents a fundamentally different cognitive layer.

This is how professional writers have always worked. While everyone else assembled sentences word by word, writers also learned to grab entire paragraphs and slide them around like puzzle pieces. They'd lift a 300-word argument from draft three and drop it into section two of draft seven. What used to be specialized craft knowledge is now universal literacy.

Most people still haven't realized the competition has moved. They're polishing sentences or short prompts while the real value has shifted up to architecting text ecosystems. The AI early adopters get this. Everyone else is fighting the wrong battle.

English Is The New STEM

The economic ground is shifting under our feet right now. An entire generation is being prepared for jobs that won't exist. The primary focus of the last several decades has been the STEM fields, and that focus is about to become completely mismatched. Science and engineering built the world we live in, but AI is about to flip the entire value equation.

Make no mistake, STEM skills are still necessary. It's just that they're no longer differentiators. They're table stakes. You have to have them, have to understand the abstractions and the models. But it's no longer where the action is. Mental calculation is still useful even if you have a calculator, but detailed calculation has been commodified. And code is being commodified. Words and sentences too. We call what AI writes "slop" but there's a level of cope to this. Right now is the worst these tools will ever be and they can still knockout some killer sentences. Maybe not at the level of a Cormac McCarthy or CS Lewis, but neither could their younger versions. The value is moving up the chain, from the base elements like numbers and words, up to abstractions like algorithms and text.

This is a new type of literacy. It's a way of thinking about ideas and tokens at one level up from sentences. My incredibly sloppy voice memo with all sorts of spew is useful. It doesn't matter that it's not linear or that it has a bunch of ridiculous sentence fragments. What matters is the ideas - which might be good or bad. But when they're good, I can pull them apart and use AI to help me re-form them into something that works. I'm manipulating tokens.

One surprising corollary is how much more I use voice. I'm not a slow typist, but my typing is too slow. On a microphone, I can spit out 500 word prompts and, sure, a bunch of it will be nonsensical but as a whole prompt it's still far more useful than the perfectly crafted, perfectly argued 2-sentence prompt I used to write.

Traditional reading instruction trains kids for linear comprehension when they need architectural manipulation. We teach them to parse sentences but now they also need move up the stack and orchestrate systems of ideas. I am the loudest advocate to get kids to read more. If English is the new STEM, then the number one focus of schools should be to get every kid to an expert level of reading. But this style of thinking about text is new. It's not reading (or writing), it's architectural text manipulation. Traditional reading is linear: word → sentence → paragraph → idea. This new literacy is architectural: you grab a 500-word chunk, understand its function, move it where it serves your purpose.

When I'm working with my editor prompt, I'm not reading every word. I'm scanning for the shape of the feedback, identifying which sections contain the insights I need, then extracting and repositioning entire paragraphs as units. It's like working with LEGO blocks, except each block is a complex argument or detailed analysis.

This is pattern recognition at the chunk level rather than skimming, something that professional writers mastered long ago. Can this 200-word explanation of the problem move to the introduction? Does this 300-word argument belong in section two or section four? This is writerly thinking, applied to the age of AI.

Most people never learned to think like writers. They don't see text as architecture instead of linear sequence. They never had to reorganize 50 pages of material or combine insights from multiple sources into a coherent argument. But now that's exactly what everyone needs to do. Most people still read like they're assembling a sentence word by word. This new literacy treats coherent ideas as single manipulable objects. You grab them, evaluate their function, and place them where they strengthen the overall structure. Just like a real writer.

So it's a new world where large-scale manipulation of text and tokens is a differentiating skill that will let you articulate or build or grow the ideas that you have. Doing this well requires comprehensive skill with English and an understanding of the abstractions that make up the world of science and math.

Here's the tragedy that should keep parents awake at night: we're systematically destroying our children's capacity for the exact skill that's becoming the most valuable.

Just as the ability to read voraciously and manipulate large volumes of text becomes the core economic skill, we're giving kids dopamine machines that fragment their attention into 15-second clips. We're training them to expect instant gratification and infinite scrolling precisely when they need to develop the capacity to work with 500-word chunks as building blocks.

Not only is our educational system not enough, we're actively sabotaging the neural pathways that will let kids succeed in an AI-driven economy. Every TikTok scroll is practice for the wrong kind of thinking. Every Instagram story trains them away from the sustained attention they'll need to architect text at scale.

The window is shrinking. The kids who can't handle large volumes of text won't just be disadvantaged, they'll be economically irrelevant. The future economy is going to be built on AI. It is going to rewire everything, and it is going to be built by people that can manage and manipulate tokens at large scale. We need to prepare our kids for this world.

A New Literacy

Voracious reading is now a requirement. Get your kids to read as many books as they can. It doesn't matter what it is. It could be an encyclopedia, a Pokemon collector value guide, or the next silly fantasy novel in a series. Just get them reading and keep them reading. Avoid video, especially short-form video. I'd love to say that if your kids stay off of TikTok and Instagram that's enough. But unfortunately, all video has adopted the short, quick cuts that became famous on TikTok. These are dopamine machines and they reinforce short attention spans.

As token costs decrease, the amount of input and output between AI systems and between humans and AI is increasing. This is how we think in terms of ideas, we can slide them around as input and output now. When you're researching something, don't take notes sentence by sentence. Instead, read three articles and throw everything you can remember into a 500-word brain dump. Feed that mess to Claude and ask for the key themes and contradictions. You'll start seeing patterns across sources instead of getting lost in individual facts. Or open a long article, spend two minutes scanning it, then write a paragraph about its main argument without looking back. This is about more than reading or skimming. You're training yourself to grab the shape of ideas and not just memorize the details.

Most importantly, get comfortable feeding AI systems substantial context. Instead of asking 'What is X?', give it 5 minutes of speech or 1,000 words about what you already understand about X and ask 'What am I missing?' Your prompts should feel too long, almost embarrassingly verbose. That's a good sign.

As AI changes our world it demands a new literacy from us, one that builds on the fundamentals. This isn't a slow trend. The AI revolution is happening now, creating economic winners and losers in real time. The kids who can manipulate ideas at scale will build the future. The kids stuck at the sentence level (or worse, watching TikToks) will be left behind.

It turns out, the building blocks of ideas are just walls of text. Writers figured this out centuries ago — they focused not just on crafting sentences but on architecting ideas. Today we can translate ideas into reality in a whole new way. If you can manipulate the walls of text well, you can create a new world, convince an audience, or build a business. No other skills are necessary. Voracious reading and writing are going to be the most economically valuable skills of the next couple of decades.

It's time for all of us to become writers.