Grace Hopper's Revenge

What the machines teach us about our software tools

The world of software has lots of rules and laws. One of the most hilarious is Kernighan’s Law:

Debugging is twice as hard as writing the code in the first place. Therefore, if you write the code as cleverly as possible, you are, by definition, not smart enough to debug it.

I’ve always understood Kernighan’s Law to be about complexity—about keeping the code you write as simple as possible to reason about.

With LLMs now I’m learning it has a lot to do with language design too.

I’m still seeing a decent number of people on Twitter complain occasionally that they’ve tried AI-driven coding workflows and the output is crap and they can move faster by themselves. There’s less of these people in the world of Opus 4.5 and Gemini 3 now, but they’re still there. Every time I see this I want to know what they’re working on and what languages and libraries they’re using.

The big benchmarks for software engineers right now are SWEBench for coding and TerminalBench for computer tasks. Benchmarks are supposed to represent all coding tasks, so it’s critical to note here that SWEBench is focused on Python. TerminalBench involves more varied computer tasks, but when the agents need to write code, they write Python.

These are effectively Python benchmarks.

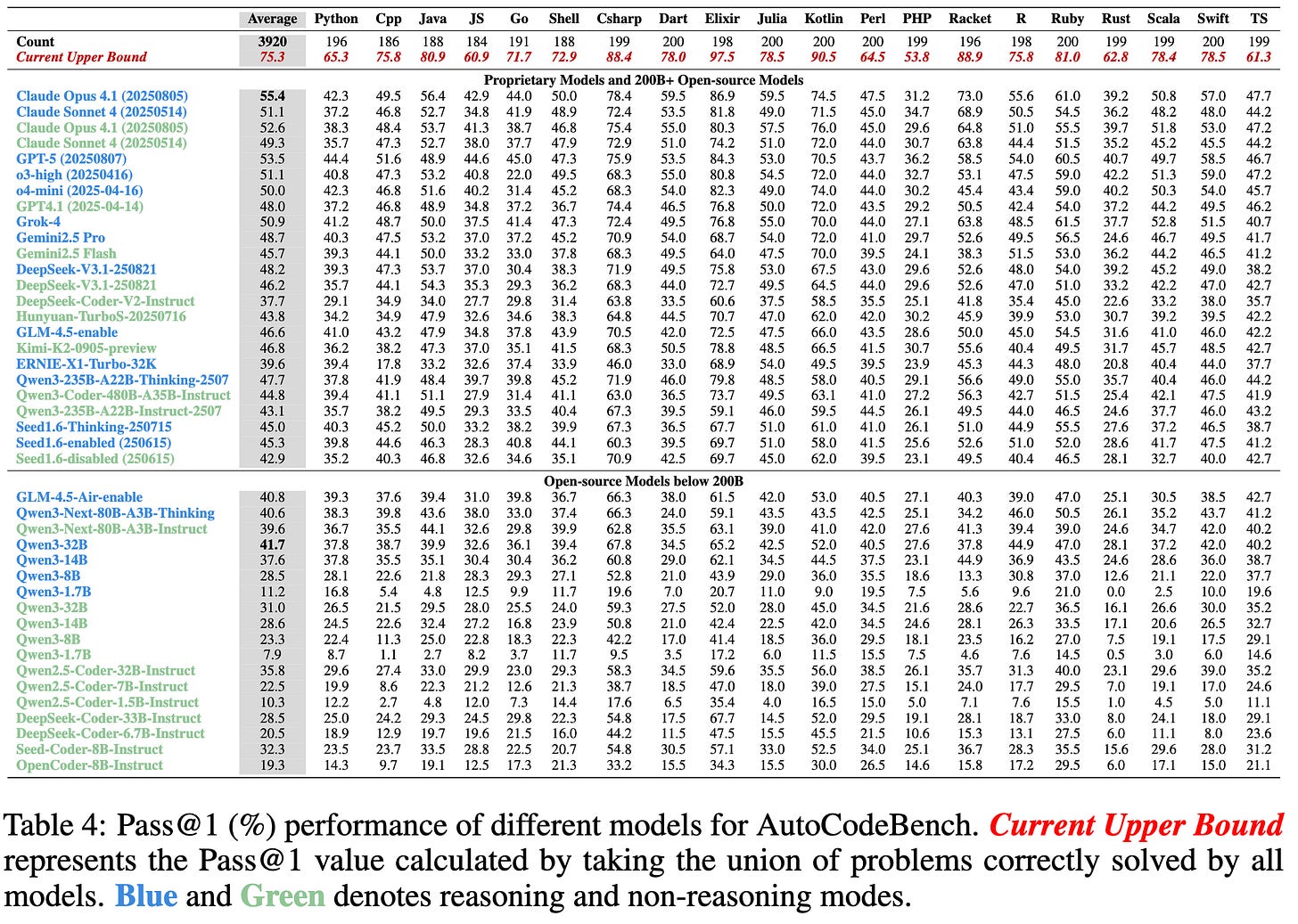

So what about other languages? Fortunately there’s AutoCodeBench, which doesn’t just test different models— it tests across 20 different programming languages. How’s that look? It looks like this:

Now, what we’ve been told about models is that they’re only as good as their training data. And so languages with gargantuan amounts of training data ought to fare best, right?

Turns out that models kind of universally suck at Python and Javascript.

The top performing languages (independent of model) are C#, Racket, Kotlin, and standing at #1 is Elixir.

I’ve been using Elixir as my primary language for a few years now, so I have obvious bias here. But this points to something critical about language design and where the nature of programming computers is going in the future. The amount of training data doesn’t matter as much as we thought. Functional paradigms transfer well1. Structure beats volume. JavaScript has the training data but fights the architecture. Elixir has less data but flows with it.

So let’s talk about Tesla.

Tesla bet on vision when everyone else was bolting LIDAR to their roofs. It seems naive—human eyes are cheap sensors fooled by glare and rain and darkness. But Tesla bet on it because roads aren’t chaotic in random ways. They’re chaotic in specifically human ways, because humans built them. Color-coded lights. Painted lines. Signs shaped like their meanings. A century of visual grammar, internalized by every driver, encoded in every intersection.

Tesla and Figure are making the same bet with robots. Humanoid form, human-shaped hands, human-scale movement. Not because it’s elegant—it’s actually harder to engineer than wheels and grippers. But humans built a world for humans. Doors are human-width. Stairs are human-height. Tools have handles shaped for palms. Build a robot that moves like we move, and a thousand years of infrastructure comes free.

This isn’t about optimizing for humans. It’s about infrastructure: optimizing for the load-bearing interfaces. For cars and robots, that’s vision and hands—because we built our physical world for eyes and fingers.

For software, the load-bearing interface isn’t actually code. Code is implementation. The load-bearing interface is ideas written in English: requirements docs, bug reports, interface specs, audit logs. Humans specify intent and verify outcomes in language. The code is just what happens in between.

Abelson and Sussman famously said “Programs must be written for people to read, and only incidentally for machines to execute.” But we’ve spent fifty years optimizing programming languages for human writing. We built objects with identity and state because that’s how we experience reality—babies develop object permanence at eight months. It felt natural. But the bottleneck was never creation. It was always verification.

When Grace Hopper originally imagined and wrote the first compiler, she envisioned the translation layer moving directly from English to machine code. 75 years later, we’re finally able to work with her original vision.

“Programs must be written for people to verify, and only incidentally for machines to execute.”

That’s a statement about accountability. Humans own the specification. Humans own the verification. Everything in between is implementation.

We humans are not very good at writing code. The machines are better and they’re the worst they’ll ever be. How good? So good that even Anthropic — which I feel quite confident in saying has some of the best coders anywhere — says that Opus 4.5 now beats all of their incoming hires on their coding tests.

The machines are better. The gulf is going to grow. But let’s consider why.

Humans remember in episodes and narratives. Not data points but scenes — sequences with befores and afters. We evolved to track an animal as it moved behind a rock, to hold in mind that the berry bush was there even when we couldn’t see it, and to construct little movies of cause and effect. No wonder we love if-then statements. No wonder we built programming languages that fake the real world and read like plots: first do this, then do that, now check if it worked. We wrote code that matched the movies in our heads.

LLMs have no movies.

Complexity exists in the codebase, yes, but the programmer needs to reason about the runtime state of the program. What does this apply to in this part of the function and how is var foo bound inside this function?

Should this be where the complexity lives? Or should it be bound up in English, in the messy, inherently narrative world of product requirements and design docs and bug reports that surround the code?

Grace Hopper would have an answer.

Now consider the differentiated skills of an LLM. They’re extraordinary pattern matchers. They find idioms across huge corpora of text, handle declared structure well, reason locally within constrained context.

And they are bad at physical space and time. This is why they needed such an insane amount of data and fine-tuning to get hands right in image and video. They are bad at narrative consistency. They are bad at maintaining large amounts of state.

What does Javascript offer? Three hours into debugging a React component and we’re five layers deep in a stack trace that tells us nothing. The error is in useEffect. Which useEffect? The one that fires on mount, or the one that fires on update, or the one that fires whenever state changes except when it doesn’t because the dependency array is lying? We have to reconstruct the entire lifecycle in our heads—what ran, in what order, which promise landed, and with what bound to this—just to understand why a button isn’t toggling. We end up performing archaeology on our own work from Tuesday.2

On the other hand, in Elixir functions are pure. You have an input, and you get an output. A function takes this shape and returns that shape. That’s it. That’s the whole story. There’s nowhere for the complexity to hide. There is no mutating state. All data is immutable. Pattern matching means that the “shape” of the data is always defined explicitly in the parameters. Combine this with multiple function heads, which feels weird at first to a human, and you get very explicit local context: this function does this thing and the data always looks the same.

To a human, object oriented programming feels natural and functional programming feels weird. Functions need translation. There’s no mug that moves; there’s a function that takes “mug at location A” and returns “mug at location B.” Deeply unintuitive to beings who evolved tracking objects through space.

Programming with objects and state are easier to write. Programming with functions and immutable data are easier to verify. This is the difference between easy and simple. When we keep adding “easy” things, we make systems overcomplex.

Code is best written with simple tools, simple primitives, and repeatable structures. It’s not just the Elixir language design that’s remarkable, it’s the entire ecosystem. In Elixir, there is one build system. One format option. There’s one library for Enums and Collections. Naming is predictable. Simplicity is a clear value and it all works. An LLM trained on Elixir sees the same patterns repeatedly.3 An LLM trained on JavaScript sees a thousand variations.

Elixir maximizes the amount of program meaning visible in local context. And LLMs are context machines.

New Models

Which brings us back to Kernighan’s Law. When we’re encouraged to write complicated state machines, we struggle to debug them because we so easily reach the edges of our cognition.

And now we have these LLMs and everyone is worried that machines will write code that humans can’t read. I don’t worry about that. But I do think about language design. LLMs can write passable Python and JS, but they write brilliant Elixir and Racket. The amount of training data doesn’t matter.

What seems to matter is locality: can the LLM see everything it needs without reconstructing state from elsewhere. Pattern matching makes data shapes explicit. Immutability means no hidden mutations. Pipes and composition mean predictable flow. One way to do things means patterns repeat.

These are the exact same features that help humans audit code. They’re what make code reviewable, debuggable, provable.

Functional languages with explicit semantics are optimized for machine generation and human verification. This is the sweet spot. And where we’re evolving.

In the past, humans have written, read, and debugged the code.

Now LLMs write code, humans read and debug. (And LLMs write voluminous mediocre code in verbose languages.)

Humans will do less and less. LLMs will write code, debug, and manage edge cases. LLMs will verify against human specifications, human audits, human requirements. And humans will only intervene when things are misaligned. Which they can see because they have easy verification mechanisms.

To do that well, we need clear contracts. Explicit effects. Testable properties. Auditable logic. Composable pieces.

These are functional programming virtues. And what makes formal verification possible. And what LLMs handle best.

I’m running Claude Code daily now, churning millions of tokens and outputting more code than I could even type in a day. It’s all Elixir, all the time, with rigorous planning documents to understand the complexity. The structure is simple and the interfaces are clear right down to the function level. If I were writing React, I’d be worried about the libraries, the component structures, how it interacted with the chosen build tool...I’d be terrified of the spaghetti soup I’d be living in.

I couldn’t go back to writing my own code at this point. Not just because it would be so much slower, but because this is so clearly better. Readable. Verifiable. It would be harder for me to write, but it’s easy to grok.

LLMs have arrived and showed us which languages are actually well-designed. The AutoCodeBench tests are a message: the “hard” languages were never hard. They were just waiting for a mind that didn’t need movies.

The future of software engineering is still dependent on humans, but we’re not writing the code anymore. Leave that to the machines, just give them good tools for the work.

The nerds who insisted on Haskell and Erlang weren’t wrong about language design. They were just early. McCarthy was the earliest: Lisp in 1958.

NVIDIA named the AI chip architecture powering all of our progress after Grace Hopper. The machines named after her finally let us see what she saw.

But it’s not just about functional programming per se. Rust performs very poorly despite being explicit, typed, and functional-ish. Why? There’s lots of state: borrow checker complexity requires global reasoning about lifetimes.

Interestingly, TypeScript (47.2%) beats JavaScript (38.6%) by ~9 points—the type system helps. But both are still bottom half. I’d bet any React specific code would score even lower due to useState mutations, useEffect dependency tracking, and lifecycle complexity.

Elixir inherits Erlang’s “let it crash” philosophy. In most languages, you write defensive code to handle every edge case: null checks, try/catch blocks, validation at every boundary. In Elixir, you write the happy path and let the supervisor tree handle failures. This means less branching logic to generate, clearer intent in the code, and fewer error-handling paths to get wrong. The LLM doesn’t have to guess which of five error-handling paradigms the surrounding code uses.