The Cost of Legibility

Where does complexity go?

In The Return of Magic, I argued we need more legible systems. That we have climbed over each other to make ourselves legible. That we’re drowning in systems we don’t understand and can’t model. That we reach for narratives and confidence men because we can’t see the machinery of our world. And that the path forward involves both making things understandable again and actually trying to understand.

But there’s a catch because legibility has a cost. We’ve paid it with our own lives; we’ve become profiles and scores and performances and likes. We’ve made our selves predictable. Systems are no different. Flatten them and something dies.

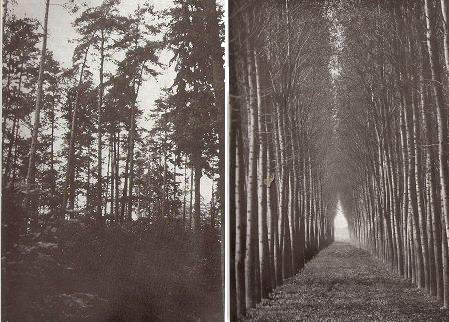

James C. Scott tells the story of German scientific forestry in Seeing Like a State. In the 18th century, foresters looked at natural forests and saw natural chaos. Trees of many types, different ages, underbrush, ground cover, all scattered without pattern. Hard to count. Hard to manage. And impossible to tax properly.

So they fixed it.

They ripped out the old growth and planted monocultures: a single species in neat rows with even spacing. A forest you could finally see and understand. Something a bureaucrat could love.

And it worked, for one generation. Then the trees started dying.

The soil went thin without its fungal networks. Pests exploded without predators. Disease spread through the genetically identical rows like fire through dry timber. Within decades, the Germans had a new word for what they’d created: Waldsterben. Forest death.

The complexity they’d removed wasn’t clutter. It was load-bearing. That tangle of chaotic disorder was doing work the foresters couldn’t see. Nature distributed work across relationships they hadn’t modeled. They deleted it and the forest died.

I want to call this: flattening.

Flattening is what happens when you take a complex system and compress it into something manageable. We do this all the time. We make something describable. Countable. A forest becomes a monoculture. A planned city is an empty grid. The irreducible human is a credit score and a bank account.

Claude Shannon taught us that this is entropy: how many bits does it take to describe the thing? Can it be compressed?

A wild forest is incompressible. Every tree a different position, species, age. You’d have to specify each one individually. “The map is not the territory.” A thing is complex when the shortest program that reproduces it is almost as long as the thing.1

Let’s describe a scientific forest: “Plant oak trees in rows, three meters apart, for two hundred hectares.” You’ve described the whole system in a tweet. Low complexity. High legibility.

And dead within a lifetime.

Flattening is compression. When you compress, you squeeze out entropy. That’s the point, that’s what makes it manageable. But there’s a law about this too. Tesler’s Law tells us that complexity is always conserved. You can move it around, but you can’t destroy it.

So when you flatten a system, the complexity has to go somewhere.

Three places.

First: it becomes secret. You think you understand the system. You’re wrong. Your model is broken and you’ve built a system waiting to break.

Second: it migrates to whoever holds the flattening tools. The state. The platform. The algorithm. They absorb what you can no longer see. This is why bureaucracies metastasize and why the hyperscalers grow more powerful. The messiness doesn’t vanish. It moves behind the curtain into systems you can’t inspect.

We’ve come close to perfecting this asymmetry. Hyperlegibility2 is pointed at you. You, the human, are maximally compressed. The algorithm has you in a few parameters: triggers, preferences, vulnerabilities, scroll velocity at 2 AM. You are describable. Predictable. A formula. The system that models you is still a black box. The complexity moved upward and now it looks down through a one-way mirror.

Third: it moves to people.

This predates our modern flattening. One of the great leaps of humanity is our ability to specialize. We let complexity migrate to experts and we trust them in their expertise.

We’ve always given ourselves social permission to defer. We expect our mechanic to understand our engine, our lawyer to understand a contract, and our cardiologist to understand the squiggly lines on that damn machine in the corner of our hospital room. Borrowed expertise is how civilization scales. The world is vast and our brains are small. When we can’t hold it ourselves, we need someone who can.

But there are two kinds of deferral.

One kind preserves agency. The expert makes complexity navigable—not simple, but traceable. We could verify if we chose to. The door stays unlocked. This is the mechanic who shows the worn part. The doctor who walks us through our options. They carry what we don’t need to carry, but we could retrace their steps if we cared to.

The other kind closes the door. The expert becomes opaque. “Trust me” replaces “here’s why.” And now we haven’t escaped magic at all—we’ve just found a new source of it. The complexity changed address. It moved from a system we couldn’t model to a person we can’t check.

In the magic essay I said: magic is what complexity looks like when models fail. When our model fails and we reach for someone else’s, are we borrowing a map or following someone we can’t verify?

Kolmogorov complexity is what models this.

Really, go read Packy McCormick’s Hyperlegibility. It is one of the most interesting ideas and trends of 2025. And while you’re at it, hit Venkatesh Rao’s 2010 piece A Big Little Idea Called Legibility too.